Brain Drain In Nigerian Healthcare

Originally written in 2018. Made small tweaks but essentially stayed on track

Here I am, discussing a very important issue crucial to the future of the health sector space, and the future of Nigeria as a country – emigration of trained personnel. It is a long read but I daresay that it is worth your time.

"In a globalised economy, the countries that pay the most and offer the greatest chance for advancement tend to get the top talent."

Migration of health workers, called ‘Brain drain’ is defined as the movement of health staff for a myriad of reasons. Brain drain may occur within countries (referred to as internal brain drain) but usually refers to cross-border or international migration and often from developing countries to developed ones (referred to as external brain drain). In Nigeria, there is an external brain drain (a mass exodus of doctors to foreign countries) and an internal brain drain (many doctors opt to work in cities like Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt.)

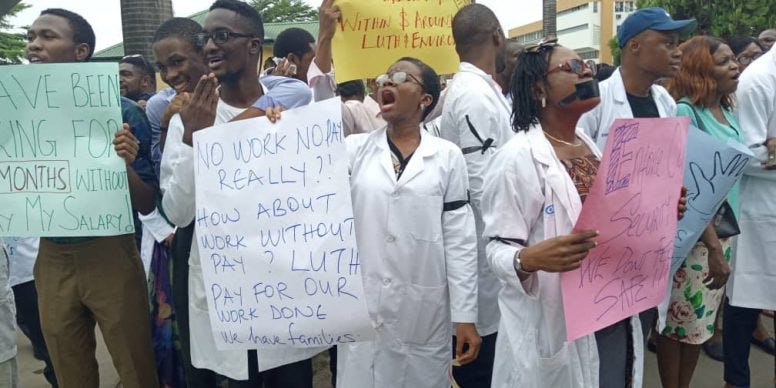

When doctors are in short supply, developed countries like the United Kingdom and the United States turn to middle-income countries to close the gap. This leaves the middle-income countries with a significant shortage of medical professionals. In Nigeria, healthcare professionals are leaving in droves. (Editor’s note: This has become tenfold worse since this article was originally published. One of the leading teaching hospitals has shut down in-patient wards due to a lack of healthcare professionals)

The migration of healthcare professionals in the Nigerian healthcare sector is not new. The trend has been on since the 80s and 90s. Back then, Saudi Arabia recruited a lot of senior health professionals and subsequently, the Middle East. There is no shortage of possible destinations for Nigerian healthcare professionals nowadays with destinations such as faraway Australia, New Zealand, UAE and even Germany (which requires learning a new language) being flirted with. In 2005, 2,392 Nigerian doctors were practising in the US alone. In the UK, the number was 1,529. The number of Nigerian medical doctors in the USA today is put at well over 4,000. Nigerian healthcare professionals are now able to seek employment in foreign countries across the globe, and it is difficult to fault them. Every Nigerian with an opportunity to ‘japa’ is doing the same.

The Nigerian healthcare sector is a mirror of the health (forgive the pun) of the nation and all our problems are magnified here. When you see a dimly lit street due to a power outage, we see the death of babies due to the absence of incubators or electricity to power them (yes, this has happened!) When you see inflated budgets detailing ridiculous expenses by the ruling class, I see CT Scans that aren’t available, unpaid and demotivated staff, neonatal units without incubators, emergency rooms without defibrillators and theatres without C-arms.

Why is this a problem?

The problem here is that medical staff are leaving the country en masse to train/work in developed countries like the US and UK (and then never returning) when already, there is a shortage of medical staff in Nigeria. A new survey conducted by Nigerian Polling organization NOIPolls in partnership with Nigeria Health Watch has revealed about 8 out of every 10 (88 per cent) medical doctors in Nigeria are currently seeking work opportunities abroad, and this finding cuts across junior, mid and senior level doctors in both public and private medical institutions such as house officers, corps members, medical and senior medical officer, residents, registrars, consultants and medical directors. The survey revealed that Nigeria has about 72,000 medical doctors registered with the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria, albeit not an updated list but only 35,000 of them are working in Nigeria.

According to Prof. Folashade Ogunsola, former provost of the College of Medicine, University of Lagos and current vice chancellor of the University of Lagos, Nigeria; we need about 13,700 doctors to be able to meet up with the World Health Organisation’s benchmark. This will require about 100 years for Nigeria to be able to meet the recommended target of the World Health Organisation (WHO) due to the population explosion and lack of commensurate increase in medical schools and teaching hospitals. Nigeria needs about 303,333 medical doctors now and at least 10,605 new doctors to join the workforce annually to meet the modest standards set by the WHO for its about 220 million citizens.

What causes brain drain?

Two main contributory factors influence the migration of medical staff;

1. Push factors: These factors push the said professionals to seek employment in other countries. These factors may include but are not limited to poor prospects for further or speciality training, poor pay, high taxes and deduction from salary, inadequate equipment and other supplies at health facilities, heavy patient burden, poor quality of life, corruption, favouritism in appointments and employments, work-related hazard (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, Hepatitis etc.), political instability/ethnic strife/insecurity, a lack of social and basic amenities, insecurity, overwhelming poverty, lack of opportunities for children and intellectual stagnancy due to isolation from current medical research.

2. Pull factors: These factors are incentives from the desired destinations that migrants find alluring and strong enough to pull them to these countries. These factors include vastly greater compensation, prospects for further training, better lifestyle, access to modern facilities, political stability, and cutting-edge research and technology.

What are the losses for Nigeria?

Loss of health services: In a pre-existing shortage of medical staff, migration only worsens the fate of the average Nigerian. It may not be apparent in cities and urban areas that there is a shortage of medical staff, but rural areas are severely affected.

Investment in human capital: The cost of training a medical doctor varies across each country in sub-Saharan Africa; however an average of US$ 65,000 was estimated as the cost of a single medical doctor (about a decade ago). All this is lost when a single doctor migrates; a loss for their country of origin.

Heavy patient load: Due to a severe shortage of medical staff, there are greater risks of exposure to wrong treatment, misdiagnosis, and poor quality of service on account of overworked remnant staff, contributing to stress, fatigue, and perhaps medical errors. Additionally, little time is spent with each patient, which may limit the full exploration of the patient's clinical condition. The available staff will be unable to keep up with the seemingly endless flow of patients near death.

Poor continuity: Replacing constantly moving medical personnel increases staff turnover rate which leads to a loss of institutional memory and continuity of care, ideals and values. Progress is halted for the adjustment of the new staff to the tradition of the institution.

Erosion of the middle class: Medical professionals make up a large chunk of the middle and upper class of society and their emigration leaves a gap which causes economic and cultural problems in developing countries.

Are there any gain(s) for Nigeria?

There are acute negative effects of the emigration of medical professionals from Nigeria and of course, positive effects.

• Brain gain: Returning migrants bring with them new sets of skills and innovations that drive the home country’s economic and professional growth.

• Increased availability of services: “The Nigerian dream is to leave Nigeria”. In India, migration opportunities are said to have made the nursing profession more attractive and to have generated an increase in the production of nurses which has raised domestic availability. With the opportunities available for migration in the medical profession, many have turned to it as their way of fulfilling the Nigerian dream. Ergo, increasing the amount of medical staff offering services.

• Remittances: It is impossible to say how much health workers remit and whether they remit more or less than other migrants. It has however been shown that remittances have driven up the spending power and quality of life in the families of migrants which by extension has helped the economic growth of the home country. For example, Tongan and Samoan nurses in Australia remit on average USD 2,688 per annum and this amount exceeds the initial investment in their training and remains constant over time.

What is the way forward?

“Some nations will grasp this reality [of international migration as inevitable] and creatively work with migrants and migration. Others will lag, still seeking restrictive measures to control and cut the level of migration. The future certainly belongs to the former”.

This is a very difficult topic to address because of the complex nature of the problem. The solution therefore is multifaceted stretching beyond the spheres of healthcare to national policies and governance. After all, health is but a section of the sectors of the nation. Many models have been postulated to attempt a reversal of brain drain across the globe and there have been success stories amidst failures - maybe because even if one adjusts the push factors, it may be outside one's domain to adjust the pull factors. In any case, the health budgets over the years suggest that healthcare is not quite the priority of the different national governments.

Training of medical personnel is usually done in a universal language e.g. English language. Some countries having studied the dynamics of migration experimented with models like changing the language of training to a local language - instead of English. This change has been a success, as seen by a decline in the number of migrants in Thailand, they experienced the lowest emigration rates ever when the training language was changed to Thai. However, this will be difficult to do in a multicultural country like Nigeria and may lead to a tribal and political tussle in the selection of a single language (No single language is spoken more than the English language across the country and among all 250+ ethnic groups in Nigeria).

A system where medical professionals are made to serve a compulsory term of one to two years, “serving” the nation has been suggested (e.g., South Africa). However, these measures have not only been counterproductive, but it also fostered the will to leave to these doctors. Flinging young vibrant doctors to faraway rural hospitals with restrictive hospital and social services as well as low pay only destroys the hope they may have in staying behind.

Analysts also proffer some sort of “tax” on medical professionals to offset some economic loss suffered by the country which when channelled to the sending country’s healthcare system will improve healthcare delivery in a myriad of ways. This is faulty in some ways but in a system plagued by corruption, it is a failure from the outset. Also, it seems unfair to doctors knowing that other skilled staff had subsidised education and have no restrictions whatsoever in their will to migrate. As such, ethical and human rights issues arise which makes this perhaps the worst option of all.

A reduction in workload is even more recalcitrant than pay levels since the physician shortage produces huge demands on medical professionals, especially in rural areas. Until there are larger numbers of physicians, it will be almost impossible to lower the demands made on them for extremely long hours and heavy workloads

Training “auxiliary” medical professionals to fill the ever-increasing vacancies in healthcare has been mooted as a possible go-to option. Here, students from rural areas are enrolled in colleges to undergo abridged training to turn them into auxiliary nurses wherein, they can be sent back to their communities or other rural areas (stemming the internal brain drain) and help improve health delivery and indices. This has been heavily criticised by many, especially by the medical guild as a purposeful move to demean medical education by training “second-rate” professionals and by putting the population at risk of further healthcare crises by leaving them to the whims of “second-rate” professionals. Today, there already exists a huge number of clinics and maternity homes operated by less qualified people which caters for about 60% of all medical cases in the country. The question is, what is more important; the colour of the cat or its ability to catch mice?

The solution shouldn't be geared towards increasing the basic salaries of healthcare professionals alone, because a salary increment may mean much but by the next day, inflation will take away all that comes with the salary hike. We should rather improve the factors pushing them away.

The first and most obvious response to brain drain is to increase job satisfaction in the current group of doctors in the country. This is directly linked to remuneration and the regularity of it. I cannot count on both hands the number of times strike actions have been organised because of poor pay or unpaid salaries (once, doctors in a certain hospital were owed salaries for 6 to 12 months).

Furthermore, an increase in the number of seats in medical school. It seems straightforward that educating more physicians will result in larger numbers overall, even if the percentages of those leaving do not change. Most of the medical schools are unable to handle the teeming population of interested students nor are they able to proffer world-class training. They are also on the brink of infrastructural breakdown. This means that more teaching hospitals will also need to be built. Policymakers and the federal government must work at creating more teaching hospitals across the federation which solves several pressing problems:

1. More employment opportunities for medical professionals: With new hospitals comes the need to employ professionals as well as other staff which will cut the unemployment rate in the country – a double-edged knife. It is usually unsettling to many to read that even in the middle of this crisis, there are fully qualified doctors in Nigeria without full-time/regular jobs.

2. More residency spaces for postgraduate education: According to the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria, there ought to be one consultant to about four resident doctors. This is not the case in any teaching hospital across the country you choose to look at.

3. More slots for medical students: I trained at an institution that could cater for far less than we were. Built in the early ‘60s, the number of students has now reached thousands from the modest tens at the start. Academic, housing and clinical facilities are now stretched thin by the overpopulation.

4. Less waiting times at the current hospitals: Patients travel for an average of 7 to 18 hours to attend a clinic, moving from one state/region of the country to the other due to the dearth of the facilities and care needed in their state/region. They wait for an average of 3 to 5 hours to finally be seen by the doctor (for a session that might be as long as 15 minutes due to the nature of the disease or the sheer number of patients waiting). The creation of new teaching medical schools and by extension, hospitals will not only cut the waiting time and travel time for patients, it will also cut the workload on the staff of hospitals, a key reason identified in the dynamics of the brain drain.

Attracting the numerous Nigerian medical staff in the diaspora must be on the cards. Many, when faced with the prospect of returning home in the face of economic and professional development like what is obtainable overseas, will take the opportunity to return to the country, as was the case in China, India, and Pakistan. This reverse brain drain will be of great value to us. However, while we still struggle to keep our country barely afloat, it seems like a Herculean task and keeping the medical staff that are still here back home clearly is the priority.

Conclusively, wholesale changes in the policies made by the federal government aimed at addressing the aforementioned problems as well as social problems pushing away medical professionals are the keys to forestalling a total disaster in our healthcare sector over the next few years. In the event of a no-show by the government, we may be left to lick our wounds as our ailing health sector finally crumbles which is unfortunately impending.